In Detecting Memory Leak in Python, scenarios were shown where python does not release memory when we created a huge list and then explicitly deleted it. The given explanation was that python caches these objects and does not release the memory back to OS. Let’s take a deeper look at what exactly happens!

Update:

I gave a talk at PyCon 2019 on a similar subject, if you prefer detailed explanation in video format, checkout PyCon19 India: Let’s Hunt a Memory Leak or just scroll down to the bottom of the page.

Python 2.7.15 (default, Jan 12 2019, 21:07:57)

[GCC 4.2.1 Compatible Apple LLVM 10.0.0 (clang-1000.11.45.5)] on darwin

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> import os, psutil, gc, time

>>>

>>> l=[i for i in range(100000000)]

>>> print(psutil.Process(os.getpid()).memory_info())

pmem(rss=3244871680L, vms=7824240640L, pfaults=1365384, pageins=460)

>>>

>>> del l

>>> print(psutil.Process(os.getpid()).memory_info())

pmem(rss=2509352960L, vms=6964514816L, pfaults=1381131, pageins=460)

After deleting the list explicitly, the memory usage still is at 2.5G. That means the integers are still floating around. (see what I did there?)

Python Objects

Everything in python is an object, including our beloved integer.

// Include/object.h

/* Nothing is actually declared to be a PyObject, but every pointer to

* a Python object can be cast to a PyObject*. This is inheritance built

* by hand. Similarly every pointer to a variable-size Python object can,

* in addition, be cast to PyVarObject*.

*/

typedef struct _object {

PyObject_HEAD

} PyObject;

// Include/intobject.h

typedef struct {

PyObject_HEAD

long ob_ival;

} PyIntObject;

So PyIntObject is just a wrapper around a C type long, with added python specific HEAD struct which contains additional information like reference count, pointer to various methods which will be called when we do print, delete, get, set, etc on the object.

Let’s try to allocate an integer:

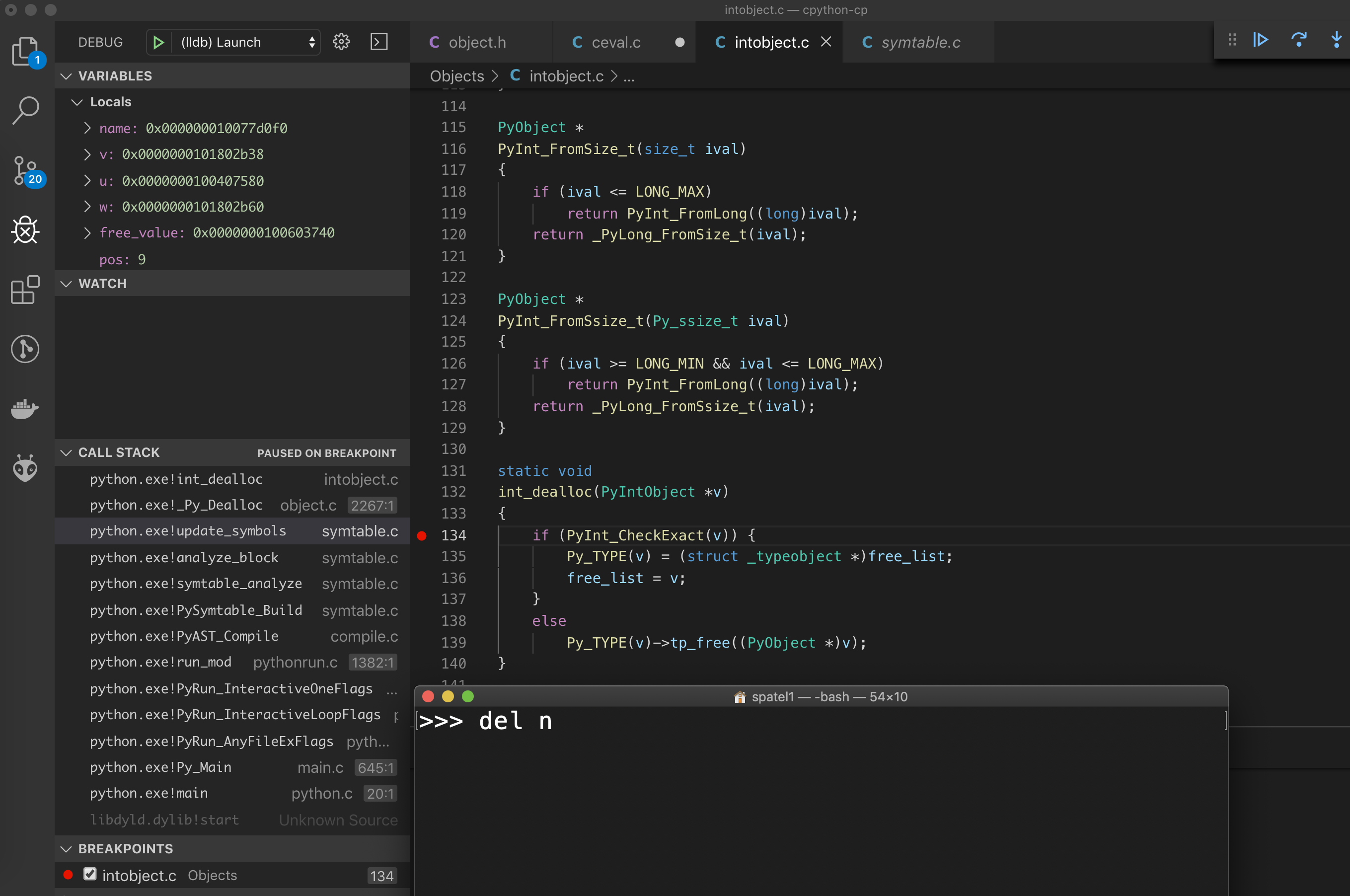

We execute a really simple python assignment statement and we can see that the function PyObject * PyInt_FromLong(long ival), which takes a long variable and returns a PyObject (of course). From this point onwards, we will dive deep into two things:

- Look deeper into the said function above, and see how exactly an object is allocated

- Look into what happens when we delete it and try to understand the behavior we saw in the beginning

Also: did you look at the call stack? The int object is created when the code is being compiled to bytecode! (The AST [abstract syntax tree] function calls) And not at during run time.

1. Creating The Int Object

PyObject *

PyInt_FromLong(long ival)

{

register PyIntObject *v;

// TRIMMED SOME CODE HERE

if (free_list == NULL) {

if ((free_list = fill_free_list()) == NULL)

return NULL;

}

/* Inline PyObject_New */

v = free_list;

free_list = (PyIntObject *)Py_TYPE(v);

(void)PyObject_INIT(v, &PyInt_Type);

v->ob_ival = ival;

return (PyObject *) v;

}

The code above is responsible for creating an integer object from given long value. The trimmed code in the snipped above handles small integers separately. Leaving some links in the bottom if you’re interested in the specifics.

So the first thing that happens here is filling some sort of free list. Let’s take a look at what it is.

/* Integers are quite normal objects, to make object handling uniform.

(Using odd pointers to represent integers would save much space

but require extra checks for this special case throughout the code.)

Since a typical Python program spends much of its time allocating

and deallocating integers, these operations should be very fast.

Therefore we use a dedicated allocation scheme with a much lower

overhead (in space and time) than straight malloc(): a simple

dedicated free list, filled when necessary with memory from malloc().

block_list is a singly-linked list of all PyIntBlocks ever allocated,

linked via their next members. PyIntBlocks are never returned to the

system before shutdown (PyInt_Fini).

free_list is a singly-linked list of available PyIntObjects, linked

via abuse of their ob_type members.

*/

#define BLOCK_SIZE 1000 /* 1K less typical malloc overhead */

#define BHEAD_SIZE 8 /* Enough for a 64-bit pointer */

#define N_INTOBJECTS ((BLOCK_SIZE - BHEAD_SIZE) / sizeof(PyIntObject))

struct _intblock {

struct _intblock *next;

PyIntObject objects[N_INTOBJECTS];

};

typedef struct _intblock PyIntBlock;

static PyIntBlock *block_list = NULL;

static PyIntObject *free_list = NULL;

static PyIntObject *

fill_free_list(void)

{

PyIntObject *p, *q;

/* Python's object allocator isn't appropriate for large blocks. */

p = (PyIntObject *) PyMem_MALLOC(sizeof(PyIntBlock));

if (p == NULL)

return (PyIntObject *) PyErr_NoMemory();

((PyIntBlock *)p)->next = block_list;

block_list = (PyIntBlock *)p;

/* Link the int objects together, from rear to front, then return

the address of the last int object in the block. */

p = &((PyIntBlock *)p)->objects[0];

q = p + N_INTOBJECTS;

while (--q > p)

Py_TYPE(q) = (struct _typeobject *)(q-1);

Py_TYPE(q) = NULL;

return p + N_INTOBJECTS - 1;

}

There are some spoilers in the comment in the code above. There are two new variables introduced above. The block_list and the free_list. block_list is a singly linked list of bunch of PytIntObjects. free_list is the pointer to next free object in this said bunch of Int objects in a block. So here is what happens in plain English:

- Allocate a new

PyIntBlock - Add the block at the beginning of the

block_listlinked list. - Now link the linked list of those bunch of Int objects.

- Return the address of last Int Object.

Here block_list is connected using *next and free_list is linked using *ob_type which is included in each Python object’s header.

Now if we went back to the function PyInt_FromLong above, what we’re doing is attaching our new long variable to the next free slot in free_list and return it.

Why? Why do all these convoluted things? As the comment said, int objects are frequently allocated in python. So this approach allocates a bunch of int objects in one go (N_INTOBJECTS many, 24 in other words). So in one single alloc call, we reserve space for 24 objects. So that next 23 int allocations can go relatively faster!!

PyIntBlock PyIntBlock

+-----------------+ +-------------------+

| | | |

| *next+----------->+ *next +--------->

block_list+->+ objects | | |

| + | | + |

+-----------------+ +-------------------+

| |

v |

+-----+----------+ v

NULL <---------+*ob_type |

| ob_ival=NAN |PyIntObject

| |

+----+-----------+

^

|

+

21 similar objects

^ +*free_list

| |

+----+-----------+ |

| *ob_type +<------+

| ob_ival=NAN |PyIntObject

| |

+----+-----------+

^

|

|

+----+-----------+

| *ob_type |

| ob_ival=11 |PyIntObject

| |

+----------------+

2. Deleting The Int Object

So that was how a python object is allocated. Let’s see what happens when we delete it

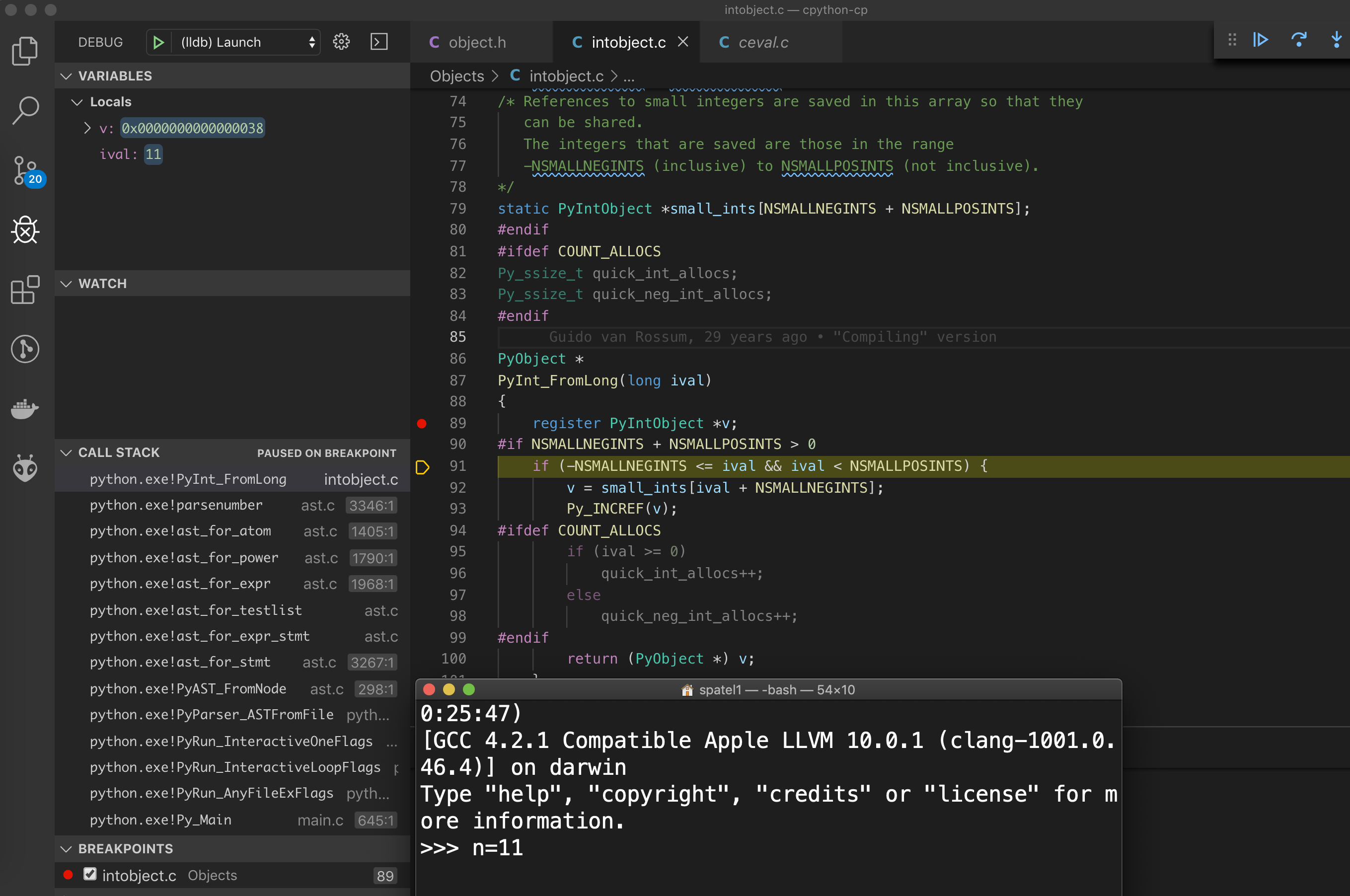

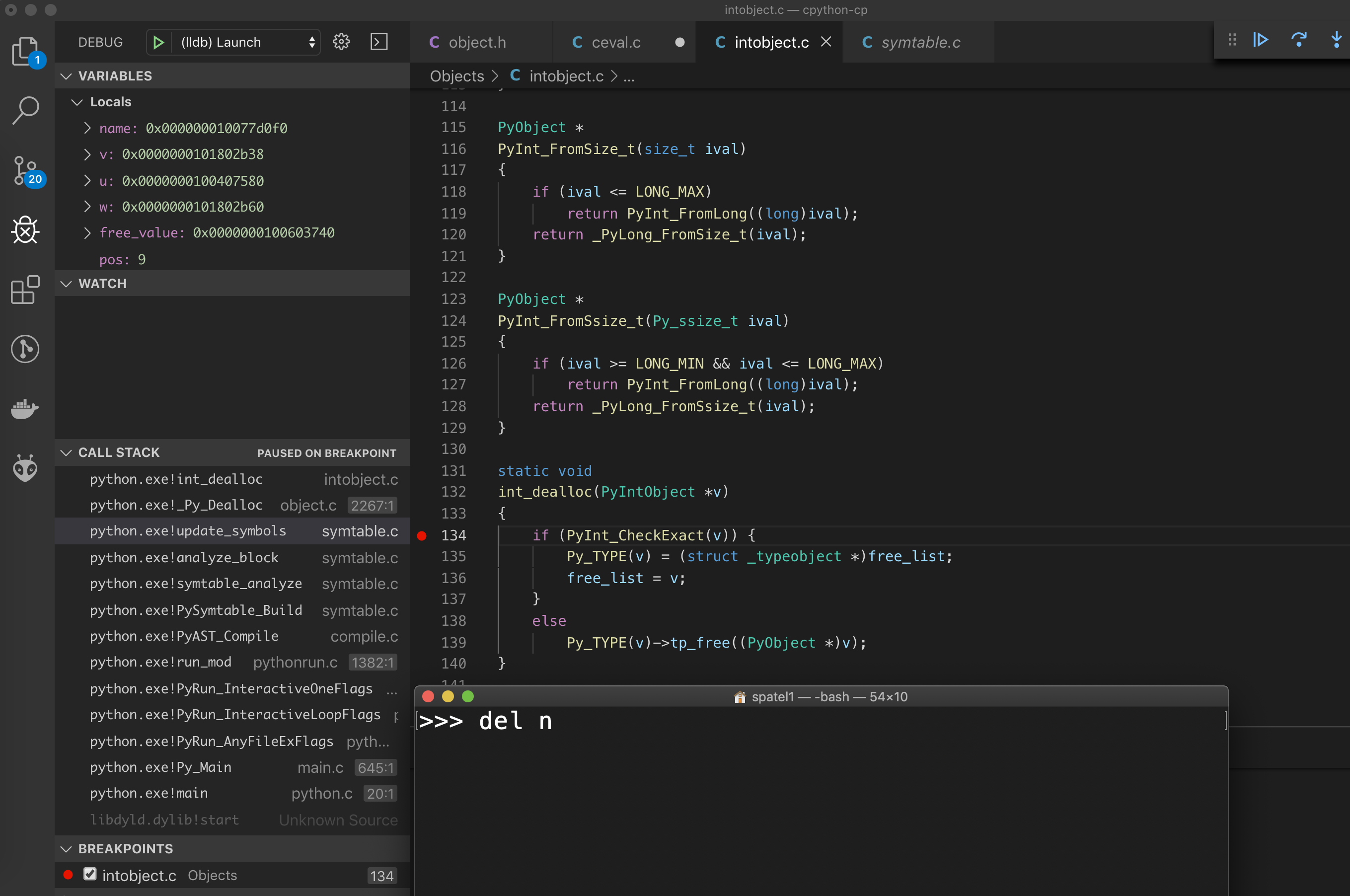

We can see static void int_dealloc(PyIntObject *v) is called. But how does python know what function to call? It is stored in the definition of PyIntObject specifically in the HEAD part. Here’s the function:

int_dealloc(PyIntObject *v)

{

if (PyInt_CheckExact(v)) {

Py_TYPE(v) = (struct _typeobject *)free_list;

free_list = v;

}

else

Py_TYPE(v)->tp_free((PyObject *)v);

}

It is relatively simple, if the given object is indeed int, then just move the free_list pointer to the deleting object.

PyIntBlock PyIntBlock

+-----------------+ +-------------------+

| | | |

| *next+----------->+ *next +--------->

block_list+->+ objects | | |

| + | | + |

+-----------------+ +-------------------+

| |

v |

+-----+----------+ v

NULL <---------+*ob_type |

| ob_ival=NAN |PyIntObject

| |

+----+-----------+

^

|

+

21 similar objects

^

|

+----+-----------+

| *ob_type |

| ob_ival=NAN |PyIntObject

| |

+----+-----------+

^

| *free_list

| +

+----+-----------+ |

| *ob_type +<----------+

| ob_ival=NAN |PyIntObject

| |

+----------------+

Bottomline:

As we saw, we allocate a bunch of int objects (inside a block) when we create a new int and there’s not enough space in the current block. But when we delete, we just move the free_list pointer around. And not call actual dealloc function to free any memory. So that explains the initial behavior!

Also, floats work the same way.